VOL #4

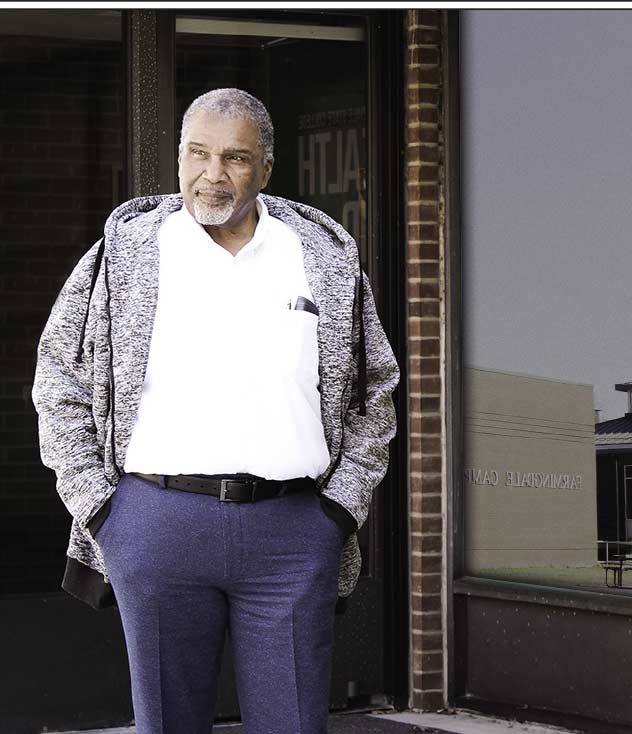

A pivotal moment in higher education occurred in March 2020, when COVID-19 shut down the NY tristate area, and Long Island in particular was hit hard. In his dual position as VP of Student Affairs and Chief Diversity Officer at Farmingdale State College (FSC), Dr. Kevin Jordan found himself at the center of this storm. We arranged to speak with him about his role in addressing this unprecedented crisis at one of Long Island’s largest public colleges. The campus and teaching halls seemed empty on the warm and bright autumnal school day when we arrived. Sensing our surprise at visiting a school without a student in sight, Dr. Jordan flashes a knowing smile:

“Believe me, there is a lot of activity going on here. The campus may look like a ghost town, but faculty and students are mostly all online right now.”

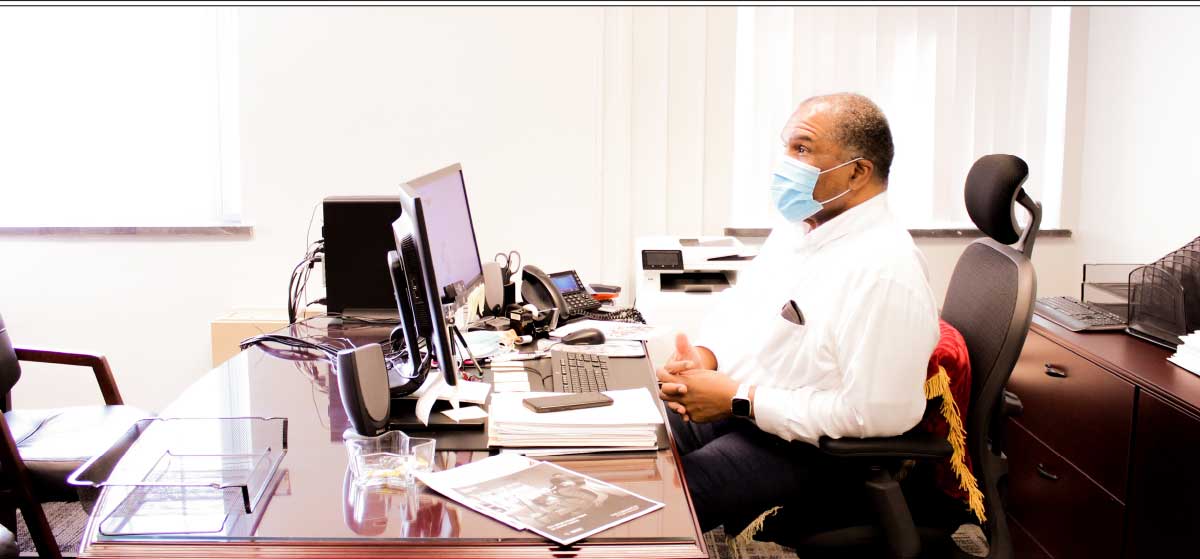

Dr. Jordan’s smile fades when he sits at a large desk crowded with stacks of reports and a long row of neatly handwritten sticky notes that symmetrically line the base of his computer. His walls are relatively bare. There are no framed diplomas featuring the degrees he earned from Princeton and Columbia’s Union Theological Seminary or the EdD he earned at while working and teaching at Dowling College. Resting against a crimson pillow that supports his lower back, he fixes us with an intense gaze and begins to discuss the challenges his campus community has encountered since coronavirus first rocked the foundations of higher education nationwide. “We were in a state of shock when the pandemic first arrived, but our leadership team had no choice but to move forward together. We only had a week to develop and then implement a plan to responsibly shut down the campus and move all learning online. We had to rely on teamwork to make changes that have impacted thousands of students, faculty and staff.”

To finance this widescale testing operation, FSC forged a partnership with Enzo Biochem, who agreed to supply the molecular and antibody testing needed for the start of the fall semester. The Health and Wellness Center’s protocol consists of weekly pool testing for approximately three random groups of 12 (e.g. faculty, staff and commuter students), as well as biweekly testing for all residential students (100 total). Residence Life works closely with campus health services, ensuring designated dorm space for students living on campus who need to isolate. To provide support for the intake processes, the Center has hired FSC work-study students to greet testers and assist with organizing their paperwork. Contact tracing is coordinated with the Suffolk County Department of Health.

To finance this widescale testing operation, FSC forged a partnership with Enzo Biochem, who agreed to supply the molecular and antibody testing needed for the start of the fall semester. The Health and Wellness Center’s protocol consists of weekly pool testing for approximately three random groups of 12 (e.g. faculty, staff and commuter students), as well as biweekly testing for all residential students (100 total). Residence Life works closely with campus health services, ensuring designated dorm space for students living on campus who need to isolate. To provide support for the intake processes, the Center has hired FSC work-study students to greet testers and assist with organizing their paperwork. Contact tracing is coordinated with the Suffolk County Department of Health.

Dr. Jordan was extremely impressed with the number of people who responded to his call for volunteers to support the dedicated staff at the Health and Wellness Center. He beams with pride when describing their sense of shared purpose:

This spirit of collaboration is also evidenced in college-wide initiatives like Safe by Design, which invited students to create posters promoting health and safety protocols around COVID-19, and the Laptop Lending Program that provided needed technology for FSC students without resources so they could maintain their online learning.

Dr. Jordan notes that the fallout of COVID-19 has exposed the variety of economic and racial disparities that have always existed among college students. He likens this moment in higher education to a reckoning, pointing out that we are currently experiencing two pandemics: the virus itself and the fear it has generated. Evidence points to the fact that communities of color nationwide are most vulnerable to both. According to CDC surveillance, Black and brown people are twice as likely to become infected by COVID-19, five times more likely to become hospitalized, and two times more likely to die. Local data reflects this trend as Newsday reports Black and brown communities on Long Island have been the hardest hit by the pandemic, reporting that Hempstead and Brentwood have the highest infection rates in the region.

Dr. Jordan notes that the fallout of COVID-19 has exposed the variety of economic and racial disparities that have always existed among college students. He likens this moment in higher education to a reckoning, pointing out that we are currently experiencing two pandemics: the virus itself and the fear it has generated. Evidence points to the fact that communities of color nationwide are most vulnerable to both. According to CDC surveillance, Black and brown people are twice as likely to become infected by COVID-19, five times more likely to become hospitalized, and two times more likely to die. Local data reflects this trend as Newsday reports Black and brown communities on Long Island have been the hardest hit by the pandemic, reporting that Hempstead and Brentwood have the highest infection rates in the region.

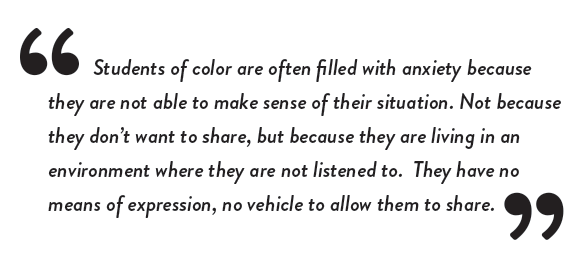

Dr. Jordan also emphasizes the significance of the psychological impact COVID 19 has had on people within these communities:

Given the current climate, it was a stroke of fortuitous vision that Dr. Jordan identified Dr. Funto Oyewole to fill a vacancy as Campus Psychologist. This hire diversified the Office of Mental Health, enabling college staff to be more responsive to the needs of the Black and brown students who make up 20% of FSC’s student population, a group that disproportionately experiences an alarmingly high rate of mental health problems. Dr. Oyewole has organized a support group for these students to talk about their feelings openly and to process their fear and trauma. Dr. Oyewole, notes Dr. Jordan, has created an environment where these students can explore and manage stress so they can persist in a school environment upended by the pandemic. “The group has become like a safe space for these students, and their freedom to express their feelings acts like a vaccine to inoculate. As a Black man working within higher education for over 35 years, I understand on a very personal level the fear these students experience. In fact, this fear pervades not only experiences of students of color but also of educators, administrators and academics of color who feel a sense of duty to act as role models for the younger generation.”

Dr. Jordan also serves on a panel of accomplished academic professionals who engage in dialog with younger Black and brown educational professionals about how to manage and cope with systemic racism. “As these young educators begin to express their thoughts and feelings, I see so much grief, frustration and trauma that they have endured within the workplace.” Dr. Jordan hesitates before continuing; he stops and starts, rephrasing cautiously before explaining how difficult it was for one of these young educators to urge administrators to make a statement in response to the George Floyd killing. However, he can’t elaborate here because he fears this educator could be publicly identified and put at risk professionally. As he sighs and reclines in his chair, it is clear to see the weight he bears for students and young educators who look like him. “Many of us experience battle fatigue. I constantly have to run my thoughts through several filters, trying to figure out how to explain things so that White people understand what I mean, all the while trying to avoid land mines. But I have to make sure that while I carefully filter out everything I want to say, I don’t ultimately filter out my own personal identity.”

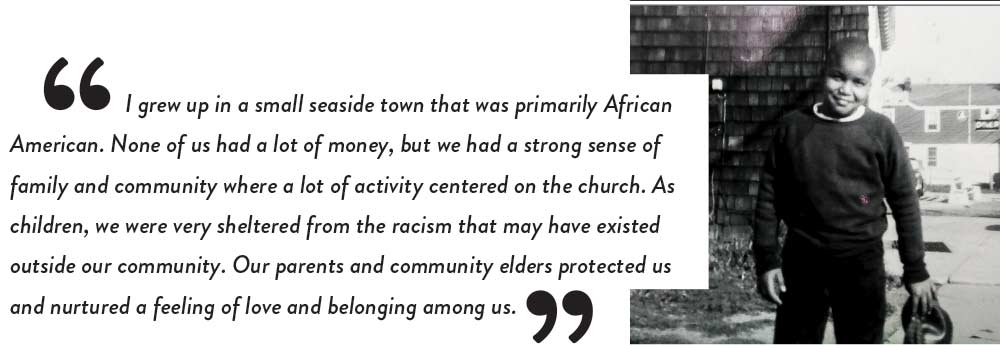

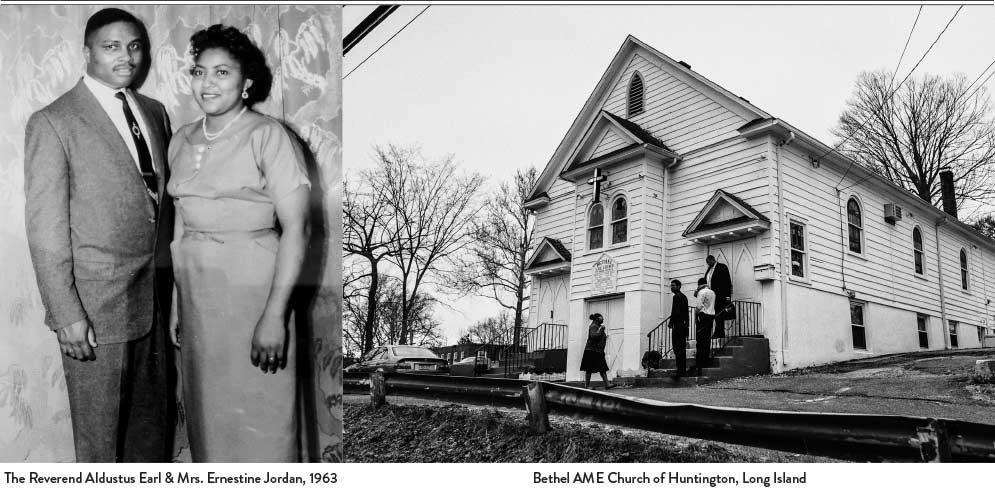

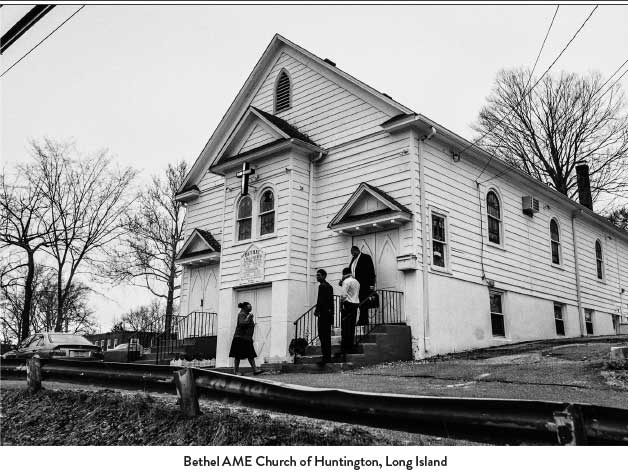

When asked how he, himself, manages this balancing act, Dr. Jordan credits his family. His father, Reverend Aldustus Earl Jordan, was a prominent pastor of Trinity AME Church in Long Branch New Jersey. Receiving many political appointments and elected to public office, he was active at the pulpit and within his community. Dr. Jordan smiles and lowers his eyes as he warmly recounts his early childhood:

Mingled with Dr. Jordan’s pride for his father’s accomplishments is a tone of sadness for the feelings he had as a nine-year-old Black boy moving to Long Island. The parsonage where the family lived was located in an all-white and unwelcoming neighborhood: “My brother and I became friends with the kids behind our house. We used to hop the fence and play in their backyard. The adults on the block often made derisive comments and enjoyed making us the butt of their jokes. They wanted to know why we lived in their neighborhood and not in Huntington Station where the other Black people lived. This type of behavior from adults was so foreign to me. I started to feel like a walking infection.”

Dr. Jordan credits his parents for giving him the strength to move forward in this hostile environment.

His mother, Ernestine, was open and honest, refusing to normalize the behavior of racist adults, or allow her children to swallow their feelings and absorb negativity. While his father openly acknowledged the injustice, Rev. Jordan would always follow up with a simple question: Now what? “No doubt the world could be unjust and cruel, but my father made it clear to all of his children that we had to learn how to survive because the world wasn’t going to change overnight.” Rev. Jordan believed change was possible, but change required an unflinching acknowledgement of what needed to be done, and his children needed to be clear-eyed and self-possessed to avoid the distractions that could derail progress. This would explain why he steered his son to study at Princeton University rather than one of the Historically Black Colleges young Kevin had his heart set on attending. His father was not dazzled by ivy-league prestige, notes Dr. Jordan, but he knew the best way to change systems was to learn them first hand:

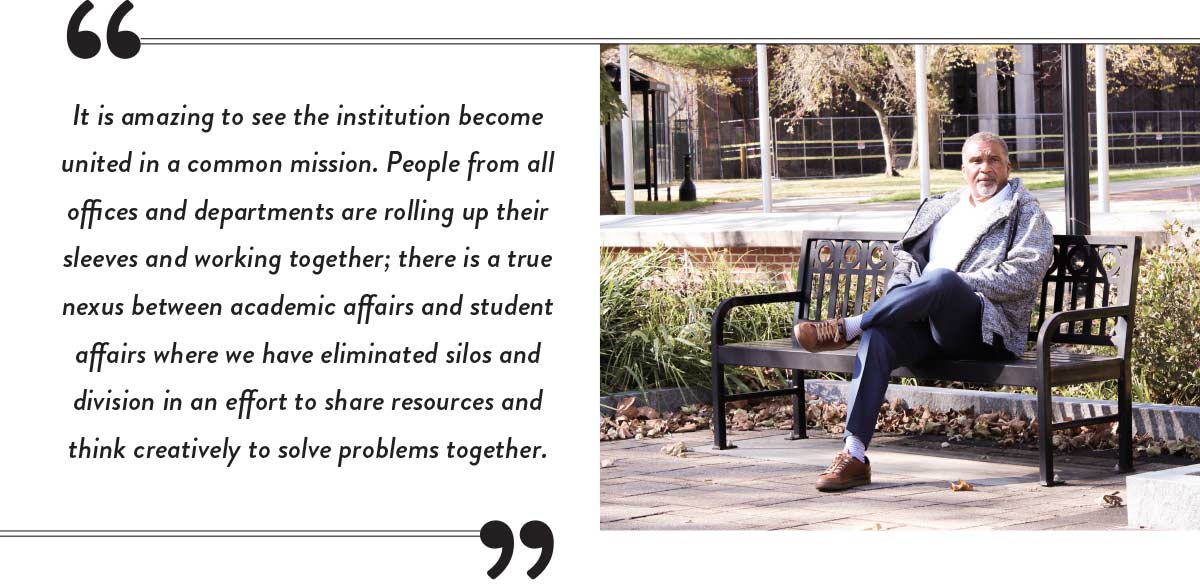

Dr. Jordan’s personal journey resonates with a collective purpose, and it informs his understanding of public health in the age of COVID-19. His current leadership position at FSC requires he work creatively with others to develop systems that support and protect the health and wellness of the entire college community. It is Dr. King’s dream of a Beloved Community that holds the key to public health for him. For Dr. Jordan, the health of a community is only as strong as its most vulnerable member, which is why it is necessary to see health through a holistic lens that accounts for the social determinants. Connectivity, notes Dr. Jordan, provides healing and solves problems. And yet where does Dr. Jordan, the individual, fit in all that? How does he maintain his own health and wellness? Dr. Jordan responds by returning to the theme of family wisdom, and begins to recall boyhood visits to his southern-born grandmother the family called affectionately called “Precious”: “Precious taught me that the best way to cook collard greens was to make sure you didn’t drain out all the water. When she took those greens out of the pot after they boiled for hours, she was careful to show how to reserve some of the liquid. You see, that water is valuable because it is filtered through the greens for so long that it’s got all the taste and nutrients. She called this liquid ‘pot liquor’ and put it in a cup for me to drink. And it’s a memory like this one, seasoned by my history, that becomes pot liquor for stories as precious to me as my grandmother’s pet name. That’s what fortifies me in times of crisis.”